History of Kruger Parks Artificial Water Points

The “Waterhole” needs no introduction to any Safari enthusiast. It’s a space and place out in the savanna that demands attention and will undoubtedly attract every single one of Africa’s wild animals. Why?, well because they have to drink and that’s where the water is.

Needless to say that the Kruger National Park with its 2 million hectares, 148 different mammals, 505 plus birds, 118 reptiles and 35 amphibians, there’s are rather obvious demand for drinking water or a place to call home. This fairly simple dynamic of species and water dependence has been at the epi-center of Kruger parks diversity management from as early as 1927.

The term Waterhole is quite vague and what is simply considered to be a place where the animals come down to drink, there are actually a variety of these artificial forms in the Kruger from boreholes with troughs to natural earthen dams and cement dams. Thought to be an absolute ecological asset, the years and the science has revealed an alternative view and effect of these “artificial water points”.

A brief history of the Kruger National Parks Waterholes:

As early as 1927 the possibility of boreholes to provide water for game during droughts was mentioned at a Parks Board Meeting. Warden at the time, James Stevenson-Hamilton however informed the Board of Trustees that he didn’t believe that boreholes were necessary as yet and for the moment this issue wasn’t raised again. This issue of water points was again raised in 1929 and although boreholes weren’t considered to be practical, it was decided that water should however be preserved in the Kruger and Warden James Stevenson-Hamilton was instructed by the board to do a survey of suitable dam sites as well as dry watercourses throughout the Park.

A few of the main reasons provided for the stabilisation of Kruger’s water supply included making the more arid central and northern regions more accessible to herbivores and to spread the game diversity more evenly of the whole of the Kruger park. Another reason was to try and keep the wildlife within the Park as it still wasn’t fenced at this time.

From 1930 the Kruger Park saw a slow yet consistent program of building natural earthen dams, which then increased dramatically by 1955 when it was anticipated that the Sabie River section would be fenced out the Kruger. The detail around this is not clear as to why but it did mean that the Park needed to have a contingency plan in place. Between 1955 and 1959, the Park built 7 dams within the region to compensate for the loss of access. In addition to that on the northern side of the Sabie River the Shimanganeni dam was built in 1960 and 11 new boreholes erected along the upper Sweni river system to replace normal pans that where lost due to drought. This was all part of a new scientific approach that was introduced into Kruger’s thinking from 1955.

During the first 20 years of implementation the new watering points, be it a borehole with a water trough or a earthen dam that captured and retained water or cement dams, all seemingly contributed to a more evenly distributed game population. This however was soon to change. What Rangers and researchers began to notice, and in particular along the western boundary of Kruger, was that the seasonal migrating species such as Zebra and Blue Wildebeest where no longer following their summer / winter grazing routes but rather adopting a shorter stop and stay between two closer regions. What became evident was that game had begun to settle and anchor around these artificial water points.

There was a degree on uncertainty around how bets to deal with this challenge as the onset of the 1960’s and 70’s saw nearly two decades of brutal droughts throughout Southern Africa with Kruger suffering and losing thousands of animals over the period. The benefit of these water points during those dry years presented a difficult challenge to argue against. If anything the opposite happened and the boreholes increased with the intention to supply more water to a drought stricken. At this point in time between 1930 and 1970 there were 299 artificial water points in place. These where made up of 268 boreholes placed across 230 sites, 36 earthen dams and 33 concrete dams.

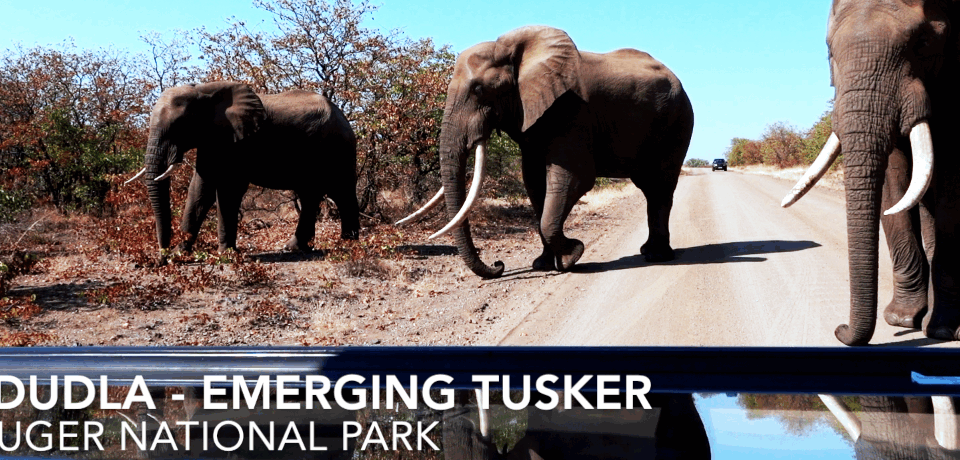

By 1975 a new picture was beginning to emerge. As more and more research was being done around certain species populations, the Park was beginning to notice that the artificial water points were having a direct effect on game. This new insight was rather startling and influenced so many studies at the time. The 1975 carnivore program noted that the proliferation of water supply in the central region of the Park around Satara, had doubled the Lion population and that the herbivores where now under significant pressure. Over a 30 year period 70 boreholes and 25 dams had been built in the central region alone. By the late 70’s the northern region now had 35 boreholes with 6 dams and was part of a park project called the “Water for Game” project. This program focused on opening up and boosting herbivore activity in areas that were in accessible due to a lack of water.

With the implementation of all these artificial water points, what was happening is that certain key species where benefiting and other where being cast into dire straights. The three species that particularly benefited were Lion, Hyena and Zebra. With such localised water, certain species began to camp out around certain water points leading to habitat destruction for other. Antelope such as Tsessebe, Roan and Sable began to suffer as the selective and niche areas where being over grazed by Zebra, Buffalo and Elephant. Without the necessary biomass to support their specific needs, these species could not thrive and a slow demise began. The Lions of course thrived as they where able to reduce their movements, focus on a few particular locations and hunt at will. With some much available the Lion population thrived thus presenting the Park with another challenge. As a result the Lion management program was implemented to help protect certain herbivore populations.

At the time this didn’t deter the artificial water program and in 1976 the eastern boundary of the KNP was fenced off with an elephant-proof fence as a result of deteriorating relations Mozambique and their current political situation. The Kruger National Park was now almost fenced in completely and the game within the parks borders where now completely dependant on the Parks biomass for survival.

As indicated by Tol Pienaar in 1985, the usual mass migration methods game used to to escape natural disasters such as droughts and fires were no longer possible and so the Park had to respond further.

A quick timeline between 1985 and 1994 :

- 1987 a concrete dam was completed in the Sabie River at Lower Sabie rest camp.

- In 1988 the Piet Grobler concrete dam was competed in the Timbavati River.

- During 1988 the first solar-energy pumps were installed at boreholes. These pumps had the advantage that they are aesthetically more appealing than windmills,

- 1990 to pump water from the weir back to the dam to ensure flowing water in a section of the Sabie River should flow cease. Fortunately it has not yet been necessary to use this system.

The reservoir and trough programme to stabilize windmills was completed in 1990. A number of free-form troughs were also constructed at windmills next to tourist roads to give a more natural appearance to the troughs.

After 1990 the Parks policy would entail a phase of consolidation that would look at phase of consolidation to eliminate the water program mistakes made in the past. With greater knowledge about the long-term and short-term rainfall cycles, animal populations, the removal of the western boundary fence and recent herbivore population dynamics, the began a process to remove water points.

In 1994 the process began and 12 boreholes were closed and one earth dam (Stangene Dam) was drained onto the basalt plains north of Shingwedzi. Since then further artificial water-points were closed in an effort to push zebra and lion off the plains and to provide more tall grass refuges for specialist grazing antelope species such as Roan, Sable and Tsessebe. This seems to have had the desired effect as zebra numbers on the plains declined and the Sable and Tsessebe numbers began to slowly stabilised.

In summary:

Since 1996 there as been a gradual process to close many water points in order to bring Krugers systems back into synergy. To date 184 water points, of which 132 are boreholes have been closed by the Park based on 76 years of research and scientifc data.

References :

Revised Water Distribution Policy for Biodiversity maintenance of KNP (Pienaar, Biggs, Deacon, Gertenbach, Joubert, Nel Van Rooyen and Venter)