The Cape Buffalo

(Syncerus Caffer)

Cape Buffalo: Africa’s Resilient Giant

The Cape Buffalo (Syncerus caffer), often called the African buffalo, is a powerhouse of the African savanna. Known for its robust build, formidable horns, and tenacious spirit, this iconic ruminant is a key player in Africa’s ecosystems and a highlight for safari-goers. This guide provides a clear, engaging, and SEO-friendly overview of the Cape Buffalo’s characteristics, habitat, history, and challenges.

Physical Characteristics

Despite standing at a modest shoulder height of 1.4–1.6 meters, the Cape Buffalo makes up for its stature with sheer mass and strength. Key features include:

-

Weight: Bulls weigh 700–850 kg, about 100 kg (220 lbs) heavier than females, who range from 550–750 kg.

-

Horns: Both sexes sport a dense crown of horns made of bone and keratin. Bulls have thicker, wider horns (up to 110 cm across) with a broad shield fully developed by age seven. Females have thinner, less prominent horns used less for fighting.

-

Coat: Calves start with a coffee-brown coat, darkening to jet black by age two. The thin, black coat attracts parasites, especially in the humid underbelly, making buffalo susceptible to ticks and other pests.

-

Build: Their short, strong legs support a solid frame, giving them a reputation as one of Africa’s toughest ungulates.

Habitat and Distribution

Cape Buffaloes are highly adaptable and thrive in diverse habitats across sub-Saharan Africa, including:

-

Riverine valleys

-

Lowland forests

-

Afro-montane escarpments

-

Marshes

-

Dry savanna woodlands

-

Vast grasslands

They require shade, water, and grazing to survive, making any cattle-suitable environment ideal for them. Historically, they dominated the African landscape. In the 18th century, they were the most abundant ungulate south of the Zambezi River, forming what early adventurer W. Cornwallis-Harris described as a “living black wall” along South Africa’s east coast to the Cape Colony. Big game hunter Frederick Courtney Selous noted in the 19th century that buffaloes outnumbered even springboks in subtropical savannas.

Historical Challenges: The Rinderpest Crisis

The Cape Buffalo’s resilience was tested in the late 1890s by the Rinderpest epizootic, a devastating plague that swept from Ethiopia to the Cape of Good Hope in 1903. This disease, transmitted by the tsetse fly, killed an estimated 95% of the Cape Buffalo population—potentially 5 million animals—along with other antelope species. Unlike domestic cattle, buffaloes have some tolerance to diseases like bovine sleeping sickness (nagana), but rinderpest was catastrophic. Over the past century, their populations have recovered, but they continue to face threats from:

-

Rinderpest: Last outbreak in 1903.

-

Foot-and-Mouth Disease: Affects grazing species.

-

Bovine Tuberculosis (BTB): Impacts buffaloes, other grazers, and predators like lions.

Ecological and Cultural Significance

As one of Africa’s most successful ruminants, the Cape Buffalo plays a vital role in grassland ecosystems. Their grazing helps maintain savanna health, and their presence supports predators like lions. Historically, their vast herds shaped the African landscape, earning them a fearsome reputation among hunters and a revered place in local cultures.

Fascinating Cape Buffalo Facts

-

Social Structure: Buffaloes live in herds, often numbering hundreds, providing safety from predators.

-

Strength: Their robust build and aggressive demeanour make them one of the “Big Five,” feared by hunters.

-

Diet: They graze on a variety of grasses, requiring ample water to support their bulk.

-

Resilience: Their immune system offers partial resistance to diseases that devastate domestic cattle.

The Cape Buffalo embodies the raw power and adaptability of Africa’s wildlife. From their historical dominance to their recovery from near extinction, these animals remain a symbol of strength and survival on the savanna. Whether you’re planning a safari or exploring African wildlife, the Cape Buffalo is a must-know species.

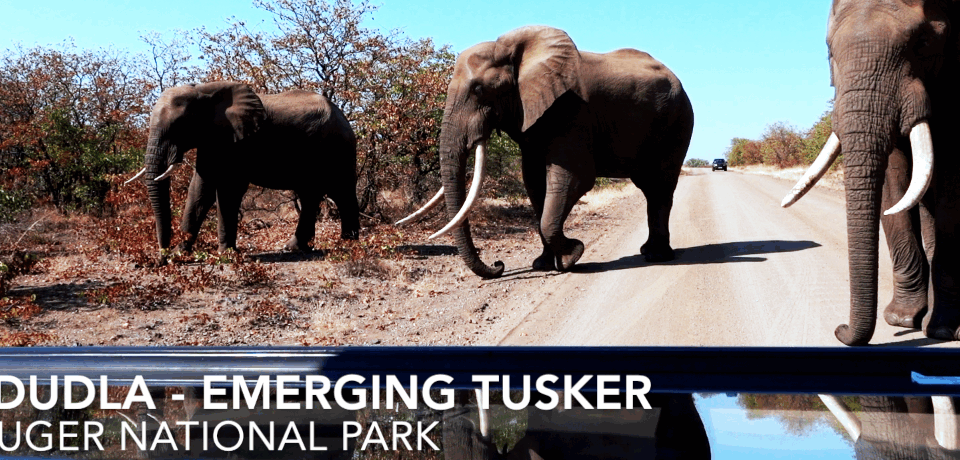

An old Buffalo Bull in the Kruger National Park© Safaria

Cape Buffalo: The Mighty Herbivore of the African Savanna

The Cape Buffalo (Syncerus caffer), a cornerstone of Africa’s “Big Five,” is a powerful and resilient herbivore known for its strength and social herds. Found across sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in Kruger National Park, this iconic ruminant captivates wildlife enthusiasts. This guide offers a clear, engaging overview of the Cape Buffalo’s origins, feeding habits, senses, behaviours, and history.

Origin of the Name

The word “buffalo” traces back to the Latin buffalus, derived from the Greek boubalos, meaning gazelle, likely referencing its ungulate form. The scientific name Syncerus, meaning “with horns,” reflects the prominent horns found on both males and females, a defining trait of this species.

Feeding Habits

Cape Buffaloes are herbivores and ruminants, favoring grasses in their diet. Key feeding characteristics include:

-

Diet: They prefer tall grasses (up to 100 cm long), which their large, four-chambered stomachs can process efficiently, unlike smaller ruminants. This allows them to consume fibrous savanna grasses.

-

Grazing Patterns: Buffaloes graze for up to 10 hours daily, spending the rest resting and ruminating (chewing cud). A 500 kg cow consumes ~18 kg of grass daily, while a large bull can eat up to 25 kg.

-

Water Needs: Their dry grass diet requires significant saliva, so they drink 30–40 liters of water daily or every 36 hours, often near waterholes.

-

Home Range: Non-territorial, buffaloes roam defined home ranges of 250–500 km² in Kruger National Park. Large herds follow seasonal routes, with grazing and trampling promoting seed dispersal and plant regrowth, shaping savanna ecosystems based on topography, soil, and rainfall.

Senses: Strengths and Weaknesses

Cape Buffaloes rely heavily on their senses to navigate their environment and avoid threats:

-

Smell: Their excellent sense of smell helps detect predators from a distance.

-

Hearing: Less developed, making them less reliant on sound for survival.

-

Eyesight: Limited with a shallow range of view, buffaloes often approach objects closely to inspect them. Cataracts are common in older individuals in Kruger National Park, particularly among aging bulls and cows.

Ruminant Digestion

As ruminants, Cape Buffaloes have a four-chambered stomach (rumen, reticulum, omasum, abomasum) for efficient grass digestion. They swallow grazed grass, later regurgitating it as a bolus for further chewing to maximize nutrient extraction. This slow process produces fine-textured dung, a hallmark of ruminants, compared to the faster hind-gut fermentation of other species.

Why Buffaloes Love Mud Baths

In Kruger National Park, it’s common to see buffaloes wallowing in muddy depressions, dubbed “elephant jacuzzis.” This behavior serves critical purposes:

-

Parasite Control: Their dark coats attract parasites, causing patchy, hairless, and sore skin, especially in older bulls. Mud baths coat their bodies, forming a protective barrier against sun and pests. When the mud dries, buffaloes rub against rocks or trees to exfoliate and manage infestations.

-

Cultural Note: Old, solitary bulls, often caked in mud, are called “Dagha Boys,” from the Zulu word dagha (mud), reflecting their cantankerous nature.

Cape Buffalo in Kruger National Park

The Cape Buffalo’s history in Kruger National Park reflects a turbulent journey of hunting, protection, and population management:

-

Historical Context: Initially hunted heavily, buffaloes were later protected but faced culling to manage overgrazing. In the 1940s, their population was a few hundred, surging to 11,000 by 1964, concentrated in the southeastern basalt grasslands near Crocodile Bridge Camp.

-

Population Boom: By 1967, an aerial census recorded 16,000 buffaloes, reaching nearly 20,000 by 1970. Favorable rains in the 1970s could have pushed numbers to 70,000 without intervention, per park biologist Solomon Joubert.

-

Culling Efforts: From 1969 to 1992, 5–10% of the population was culled annually, stabilizing numbers at ~30,000. Between 1970 and 1980, nearly 20,000 buffaloes were culled at rates of 12–20% per year.

-

Vulnerability: While buffaloes thrive in good conditions, they are susceptible to droughts, leading to sharp population declines.

Role as Prey

Cape Buffaloes are a major prey source for lions, but this wasn’t always the case. Research shows:

-

In the 1940s, buffaloes made up just 1% of lion kills, with lions preferring wildebeest, zebra, giraffe, kudu, and impala.

-

By the 1970s, buffaloes became a dominant prey species, comprising up to 60% of lion kills in Kruger’s northern region, surpassing even waterbuck.

Fascinating Cape Buffalo Facts

-

Big Five Status: Regarded as the most dangerous of the Big Five, they’ve killed more hunters than any other species.

-

Gestation: Females have a gestation period of ~340 days.

-

Teeth: Buffaloes have 32 teeth, adapted for grinding tough grasses.

-

Speed: They can run at 50 km/h and walk at 5–6 km/h.

The Cape Buffalo is a testament to resilience, thriving in diverse savannas while shaping ecosystems through grazing and movement. Whether you’re a safari enthusiast or curious about African wildlife, the Cape Buffalo’s strength and survival story make it a must-know species.

Left to right : Buffalo in the early morning sunlight, Old Bull giving a Flehman grimace as he asses the urine of a female, the buffalos best friend the Yellow-billed Oxpecker helping manage parasites.