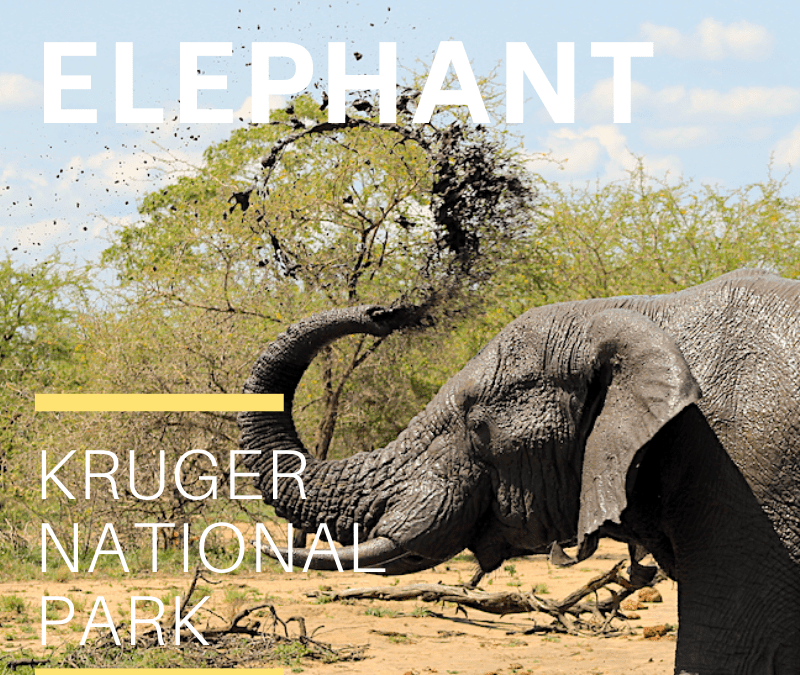

African Elephant: The Majestic Ecosystem Engineers of the Savanna

The African Elephant (Loxodonta africana), the largest land mammal on Earth, is a true icon of the African savanna. With their immense size, profound intelligence, and vital role in shaping ecosystems, these gentle giants captivate wildlife enthusiasts and play a critical role in maintaining biodiversity. This guide explores their characteristics, historical journey, population recovery, and ecological impact, with a focus on South Africa’s Kruger National Park, in a clear, engaging, and SEO-optimized format.

Overview of the African Elephant

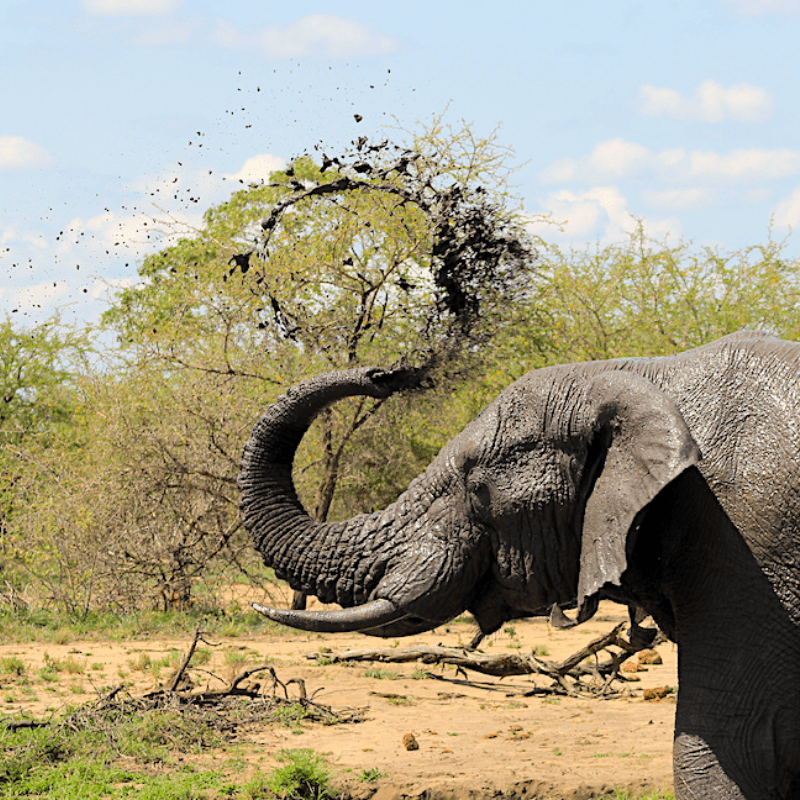

Weighing up to 6 tons, African elephants are a commanding presence in the savanna. Their large ears, long trunks, and iconic tusks make them unmistakable. Known for their intelligence and strong social bonds, elephants live in matriarchal herds led by an experienced female. Their memory and complex communication, including low-frequency rumbles, have earned them a reputation as one of nature’s most remarkable creatures.

As ecosystem engineers, elephants shape their environment by:

-

Uprooting trees to create grasslands for other species.

-

Digging waterholes that provide drinking sources for wildlife.

-

Dispersing seeds through their dung, promoting plant growth.

Historical Journey in Southern Africa

The African elephant’s story in Southern Africa is one of abundance, exploitation, and recovery:

-

Ancient Trade: As early as the 12th–13th centuries, the Mapungubwe civilization in the Limpopo Valley traded elephant ivory to Arab ports like Kilwa and Sofala, supplying markets in India and China.

-

Colonial Exploitation: By the 1780s, the Portuguese outpost at Delagoa Bay (modern-day Maputo) exported ~50,000 kg of ivory annually. In the 1800s, Boer hunters in the Transvaal shipped out 90,000 kg yearly, driving elephants to near extinction through the ivory trade and trophy hunting.

-

Near Extinction: By 1902, when Kruger National Park’s first warden, James Stevenson-Hamilton, arrived, elephants were nearly gone, with only footprints along the Olifants River as evidence of their former presence.

Population Recovery in Kruger National Park

Kruger National Park has been central to the African elephant’s comeback:

-

Early Sightings: In 1890, Frederick Kirby spotted a herd along the Timbavati River, signaling a slow return. By 1908–1920, Harry Wolhuter noted recolonization along the Letaba and Olifants rivers, with breeding herds recorded by 1938.

-

Population Growth: Aerial surveys in 1967 counted 6,500 elephants. After culling ended in the 1990s, numbers rose to 15,000 by 2007 and approximately 34,000 today, reflecting successful conservation efforts.

-

Management: Kruger’s closed ecosystem requires careful management to balance elephant populations with habitat sustainability, preventing overgrazing and tree loss.

Ecological Role: Shaping the Savanna

African elephants are vital to maintaining savanna ecosystems:

-

Grassland Creation: By felling trees, they open up areas for grazing species like zebras and antelopes.

-

Water Access: Their digging creates waterholes, benefiting smaller animals during dry seasons.

-

Seed Dispersal: Elephants spread seeds through their dung, fostering plant diversity and forest regeneration.

In Kruger, their impact is evident in the central and southern regions, where they maintain open savannas and support biodiversity.

Fascinating African Elephant Facts

-

Size: Males can reach 4 m at the shoulder and weigh up to 6 tons; females are slightly smaller.

-

Lifespan: Elephants live up to 60–70 years in the wild.

-

Diet: They consume 100–300 kg of vegetation daily, including grasses, leaves, and bark.

-

Social Structure: Matriarchal herds consist of females and calves, while males often roam alone or in bachelor groups.

-

Communication: Low-frequency rumbles travel long distances, allowing herds to stay connected.

Conservation Challenges

Despite their recovery, African elephants face ongoing threats:

-

Poaching: The ivory trade continues to endanger populations.

-

Habitat Loss: Human expansion reduces their range.

-

Human-Wildlife Conflict: Elephants raiding crops near human settlements can lead to retaliatory killings.

Kruger’s conservation efforts, including anti-poaching patrols and habitat management, are critical to their survival.

Why African Elephants Matter

African elephants are more than just a safari highlight; they are keystone species that sustain the savanna’s ecological balance. Their recovery in Kruger National Park showcases the power of conservation, while their historical journey reflects humanity’s complex relationship with nature. Whether you’re planning a visit to Kruger or exploring African wildlife, the African elephant’s majesty and ecological importance make it a must-know species.

African Elephant Populations: Guardians of the Savanna

The African Elephant (Loxodonta africana), an iconic symbol of Africa’s wilderness, is a vital ecosystem engineer shaping the savanna and forests. Divided into two subspecies—the savanna elephant (Loxodonta africana africana) and the forest elephant (Loxodonta africana cyclotis)—these majestic creatures have faced significant challenges but continue to thrive in key regions. This guide explores their population trends, ecological role, intelligence, and conservation efforts, with a focus on South Africa’s Kruger National Park, presented in a clear, engaging, and SEO-friendly format.

African Elephant Population Overview

Once numbering in the millions across Africa, African elephants have declined due to poaching, habitat loss, and human-wildlife conflict. According to the 2023 African Elephant Status Report by the IUCN, approximately 415,000 elephants remain, with savanna elephants making up the majority. Key population strongholds include:

-

Southern Africa:

-

Botswana: ~131,000 elephants

-

Zimbabwe: ~100,000

-

South Africa: ~40,000, including ~34,000 in Kruger National Park

-

-

East Africa:

-

Tanzania: ~60,000

-

Kenya: ~36,000

-

-

Central and West Africa: Forest elephants number fewer than 100,000, facing steeper declines due to forest habitat loss and poaching.

Kruger National Park: A Case Study

Kruger’s 19,485 km² ecosystem, enclosed by fences, rivers, and mountains, highlights unique management challenges. From ~1,000 elephants in 1957, the population grew at a 6% annual rate when unmanaged, reaching 6,500 by 1967 and ~34,000 today. This growth reflects successful conservation but requires careful stewardship to prevent habitat overuse.

Ecosystem Engineers: Shaping the Savanna

African elephants are dubbed “ecosystem engineers” for their transformative impact on landscapes, particularly in Kruger:

-

Foraging Impact: A 6-ton bull consumes up to 180 kg of vegetation daily. In the wet season, 50% of their diet is protein-rich grass; in the dry season, they shift to trees and leaves (15% protein vs. grass’s 5%). In northern Kruger’s mopane forests, they avoid overbrowsing toxic trees, favoring grasses to maintain balance.

-

Facilitation: By clearing thickets, elephants create pathways for smaller herbivores like impala, enhancing biodiversity.

-

Seed Dispersal: Their inefficient digestion—60% of vegetation passes undigested—produces ~100 kg of dung daily. A single dung pile can contain 12,000 acacia seeds with a 75% germination rate, compared to 12% for pod seeds, fostering savanna tree growth.

Historical Management in Kruger

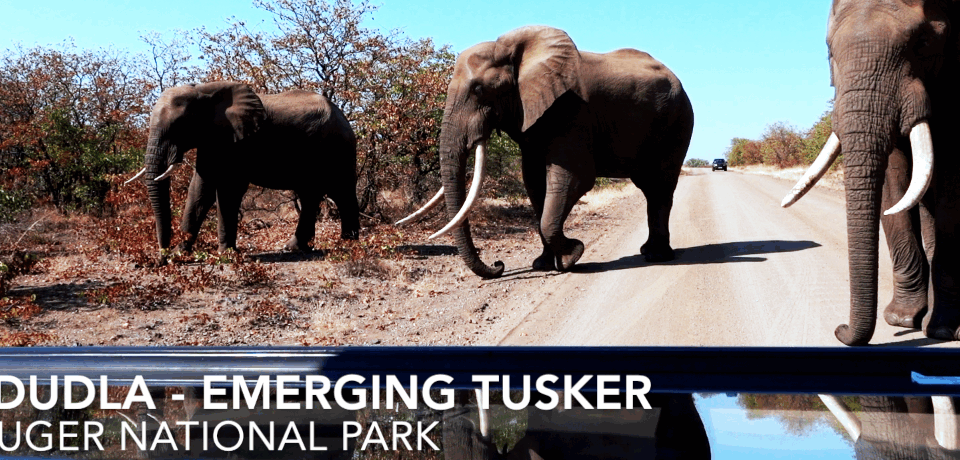

From the 1960s to 1994, Kruger culled elephants to maintain a population of ~7,000 (1 per km²) to protect vegetation near water sources and other species. By 1994, 16,027 elephants had been culled. In 1993, the removal of western fences opened 400,000 hectares of new habitat, boosting populations in areas like Sabie Sands from 70 in the dry season to 3,000 by 2007. Culling ceased in 1995, allowing natural growth.

The Intelligence of African Elephants

Recent research reveals the African elephant’s remarkable cognitive and social abilities:

-

Brain Power: Their large hippocampus and cerebral cortex enable recognition of up to 200 individuals and 100 females by call alone. Over 400 vocalizations, including infrasound, allow long-distance communication.

-

Matriarchal Wisdom: Older females lead herds, using memory to navigate to water during droughts.

-

Empathy and Cooperation: Elephants mourn their dead and show cooperative behaviors. A 2021 Nature study found they adjust foraging to reduce competition with other herbivores, promoting ecosystem health.

-

Dietary Myths Debunked: Contrary to popular belief, elephants don’t get drunk on marula fruit. With only 3% ethanol in fermented fruit and a high vitamin C content (6.9 ml/g, eight times an orange), intoxication would require impractical consumption.

Conservation Challenges and Solutions

Despite population recoveries, African elephants face ongoing threats:

-

Poaching: The ivory trade remains a significant risk.

-

Habitat Fragmentation: Human expansion limits their range.

-

Human-Elephant Conflict: Crop-raiding leads to retaliatory killings.

Conservation efforts are making strides:

-

Transfrontier Parks: Expanded habitats, like those connecting Kruger with neighboring regions, support population growth.

-

Anti-Poaching Patrols: Enhanced security reduces illegal hunting.

-

Technology: AI-driven monitoring and GPS tracking enable real-time population management.

Why African Elephants Matter

African elephants are more than majestic giants; they are keystone species sustaining savanna and forest ecosystems. Their recovery in Kruger National Park, from near extinction to ~34,000, showcases conservation success. As nature’s gardeners, their foraging, seed dispersal, and habitat creation support countless species. For safari-goers or wildlife enthusiasts, understanding the African elephant’s role as an ecosystem engineer and intelligent social creature deepens appreciation for their legacy in Africa’s wild landscapes.